I wrote this half-post as Obama was closing in on the American elections in early November:

Today I woke up in Ntinda, a sizeable suburb of Kampala, and and ate breakfast while I watched an Al-Jezeera feed about the American presidential elections. In just less than two weeks while I’ve been here, the East African media has gotten very creative with the amount of influence that an Obama presidency would have on Africa as a whole. Kenya has been particularly excited about president-elect Obama, which comes as no surprise. Many politicians in this part of the world are loyal to their families, clan mates, and fellow soldiers before anyone else.

There are few moderate voices in this hopegasm. The New Vision, Uganda’s English language daily, printed a front page banner headline last week saying, “AFRICA TO TOP OBAMA’S AGENDA.” The story they printed made me think that the entire continent has forgotten one very important detail: Obama is still American. His agenda is still going to have to respond to the constituency that elected him.

Now with three months’ distance, we are a week into the new president’s first term (and I say first because I am still audacious and hopeful). The spectre of worldwide divisions over the current Isreali conflict, the sobering picture of what the American economy will serve up for the rest of the world next, and the Iraqi quagmire exacerbating the whole thing, it seems that America’s current #1 emotional export might be more necessary in the States than anywhere else right now. So far I like the Ugandan approach: where the top choice of medium for news is usually radio, people have been listening to Obama’s inauguration speech over and over again. I’ve written before about the art of great leadership. If speech writing and delivery gives any clear indications of that art, then that oration is worth reproducing here in America’s newest preferred form of info flow.

My fellow citizens:

I stand here today humbled by the task before us, grateful for the trust you have bestowed, mindful of the sacrifices borne by our ancestors. I thank President Bush for his service to our nation, as well as the generosity and cooperation he has shown throughout this transition.

Forty-four Americans have now taken the presidential oath. The words have been spoken during rising tides of prosperity and the still waters of peace. Yet, every so often the oath is taken amidst gathering clouds and raging storms. At these moments, America has carried on not simply because of the skill or vision of those in high office, but because We the People have remained faithful to the ideals of our forbearers, and true to our founding documents.

So it has been. So it must be with this generation of Americans.

That we are in the midst of crisis is now well understood. Our nation is at war, against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred. Our economy is badly weakened, a consequence of greed and irresponsibility on the part of some, but also our collective failure to make hard choices and prepare the nation for a new age. Homes have been lost; jobs shed; businesses shuttered. Our health care is too costly; our schools fail too many; and each day brings further evidence that the ways we use energy strengthen our adversaries and threaten our planet.

These are the indicators of crisis, subject to data and statistics. Less measurable but no less profound is a sapping of confidence across our land – a nagging fear that America’s decline is inevitable, and that the next generation must lower its sights.

Today I say to you that the challenges we face are real. They are serious and they are many. They will not be met easily or in a short span of time. But know this, America – they will be met.

On this day, we gather because we have chosen hope over fear, unity of purpose over conflict and discord.

On this day, we come to proclaim an end to the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn out dogmas, that for far too long have strangled our politics.

We remain a young nation, but in the words of Scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things. The time has come to reaffirm our enduring spirit; to choose our better history; to carry forward that precious gift, that noble idea, passed on from generation to generation: the God-given promise that all are equal, all are free, and all deserve a chance to pursue their full measure of happiness.

In reaffirming the greatness of our nation, we understand that greatness is never a given. It must be earned. Our journey has never been one of short-cuts or settling for less. It has not been the path for the faint-hearted – for those who prefer leisure over work, or seek only the pleasures of riches and fame. Rather, it has been the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things – some celebrated but more often men and women obscure in their labor, who have carried us up the long, rugged path towards prosperity and freedom.

For us, they packed up their few worldly possessions and traveled across oceans in search of a new life.

For us, they toiled in sweatshops and settled the West; endured the lash of the whip and plowed the hard earth.

For us, they fought and died, in places like Concord and Gettysburg; Normandy and Khe Sahn.

Time and again these men and women struggled and sacrificed and worked till their hands were raw so that we might live a better life. They saw America as bigger than the sum of our individual ambitions; greater than all the differences of birth or wealth or faction.

This is the journey we continue today. We remain the most prosperous, powerful nation on Earth. Our workers are no less productive than when this crisis began. Our minds are no less inventive, our goods and services no less needed than they were last week or last month or last year. Our capacity remains undiminished. But our time of standing pat, of protecting narrow interests and putting off unpleasant decisions – that time has surely passed. Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America.

For everywhere we look, there is work to be done. The state of the economy calls for action, bold and swift, and we will act – not only to create new jobs, but to lay a new foundation for growth. We will build the roads and bridges, the electric grids and digital lines that feed our commerce and bind us together. We will restore science to its rightful place, and wield technology’s wonders to raise health care’s quality and lower its cost. We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories. And we will transform our schools and colleges and universities to meet the demands of a new age. All this we can do. And all this we will do.

Now, there are some who question the scale of our ambitions – who suggest that our system cannot tolerate too many big plans. Their memories are short. For they have forgotten what this country has already done; what free men and women can achieve when imagination is joined to common purpose, and necessity to courage.

What the cynics fail to understand is that the ground has shifted beneath them – that the stale political arguments that have consumed us for so long no longer apply. The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works – whether it helps families find jobs at a decent wage, care they can afford, a retirement that is dignified. Where the answer is yes, we intend to move forward. Where the answer is no, programs will end. And those of us who manage the public’s dollars will be held to account – to spend wisely, reform bad habits, and do our business in the light of day – because only then can we restore the vital trust between a people and their government.

Nor is the question before us whether the market is a force for good or ill. Its power to generate wealth and expand freedom is unmatched, but this crisis has reminded us that without a watchful eye, the market can spin out of control – and that a nation cannot prosper long when it favors only the prosperous. The success of our economy has always depended not just on the size of our Gross Domestic Product, but on the reach of our prosperity; on our ability to extend opportunity to every willing heart – not out of charity, but because it is the surest route to our common good.

As for our common defense, we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals. Our Founding Fathers, faced with perils we can scarcely imagine, drafted a charter to assure the rule of law and the rights of man, a charter expanded by the blood of generations. Those ideals still light the world, and we will not give them up for expedience’s sake. And so to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman, and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and that we are ready to lead once more.

Recall that earlier generations faced down fascism and communism not just with missiles and tanks, but with sturdy alliances and enduring convictions. They understood that our power alone cannot protect us, nor does it entitle us to do as we please. Instead, they knew that our power grows through its prudent use; our security emanates from the justness of our cause, the force of our example, the tempering qualities of humility and restraint.

We are the keepers of this legacy. Guided by these principles once more, we can meet those new threats that demand even greater effort – even greater cooperation and understanding between nations. We will begin to responsibly leave Iraq to its people, and forge a hard-earned peace in Afghanistan. With old friends and former foes, we will work tirelessly to lessen the nuclear threat, and roll back the specter of a warming planet. We will not apologize for our way of life, nor will we waver in its defense, and for those who seek to advance their aims by inducing terror and slaughtering innocents, we say to you now that our spirit is stronger and cannot be broken; you cannot outlast us, and we will defeat you.

For we know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness. We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus – and non-believers. We are shaped by every language and culture, drawn from every end of this Earth; and because we have tasted the bitter swill of civil war and segregation, and emerged from that dark chapter stronger and more united, we cannot help but believe that the old hatreds shall someday pass; that the lines of tribe shall soon dissolve; that as the world grows smaller, our common humanity shall reveal itself; and that America must play its role in ushering in a new era of peace.

To the Muslim world, we seek a new way forward, based on mutual interest and mutual respect. To those leaders around the globe who seek to sow conflict, or blame their society’s ills on the West – know that your people will judge you on what you can build, not what you destroy. To those who cling to power through corruption and deceit and the silencing of dissent, know that you are on the wrong side of history; but that we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.

To the people of poor nations, we pledge to work alongside you to make your farms flourish and let clean waters flow; to nourish starved bodies and feed hungry minds. And to those nations like ours that enjoy relative plenty, we say we can no longer afford indifference to suffering outside our borders; nor can we consume the world’s resources without regard to effect. For the world has changed, and we must change with it.

As we consider the road that unfolds before us, we remember with humble gratitude those brave Americans who, at this very hour, patrol far-off deserts and distant mountains. They have something to tell us today, just as the fallen heroes who lie in Arlington whisper through the ages. We honor them not only because they are guardians of our liberty, but because they embody the spirit of service; a willingness to find meaning in something greater than themselves. And yet, at this moment – a moment that will define a generation – it is precisely this spirit that must inhabit us all.

For as much as government can do and must do, it is ultimately the faith and determination of the American people upon which this nation relies. It is the kindness to take in a stranger when the levees break, the selflessness of workers who would rather cut their hours than see a friend lose their job which sees us through our darkest hours. It is the firefighter’s courage to storm a stairway filled with smoke, but also a parent’s willingness to nurture a child, that finally decides our fate.

Our challenges may be new. The instruments with which we meet them may be new. But those values upon which our success depends – hard work and honesty, courage and fair play, tolerance and curiosity, loyalty and patriotism – these things are old. These things are true. They have been the quiet force of progress throughout our history. What is demanded then is a return to these truths. What is required of us now is a new era of responsibility – a recognition, on the part of every American, that we have duties to ourselves, our nation, and the world, duties that we do not grudgingly accept but rather seize gladly, firm in the knowledge that there is nothing so satisfying to the spirit, so defining of our character, than giving our all to a difficult task.

This is the price and the promise of citizenship.

This is the source of our confidence – the knowledge that God calls on us to shape an uncertain destiny.

This is the meaning of our liberty and our creed – why men and women and children of every race and every faith can join in celebration across this magnificent mall, and why a man whose father less than sixty years ago might not have been served at a local restaurant can now stand before you to take a most sacred oath.

So let us mark this day with remembrance, of who we are and how far we have traveled. In the year of America’s birth, in the coldest of months, a small band of patriots huddled by dying campfires on the shores of an icy river. The capital was abandoned. The enemy was advancing. The snow was stained with blood. At a moment when the outcome of our revolution was most in doubt, the father of our nation ordered these words be read to the people:

“Let it be told to the future world…that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive…that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet [it].”

America, in the face of our common dangers, in this winter of our hardship, let us remember these timeless words. With hope and virtue, let us brave once more the icy currents, and endure what storms may come. Let it be said by our children’s children that when we were tested we refused to let this journey end, that we did not turn back nor did we falter; and with eyes fixed on the horizon and God’s grace upon us, we carried forth that great gift of freedom and delivered it safely to future generations.

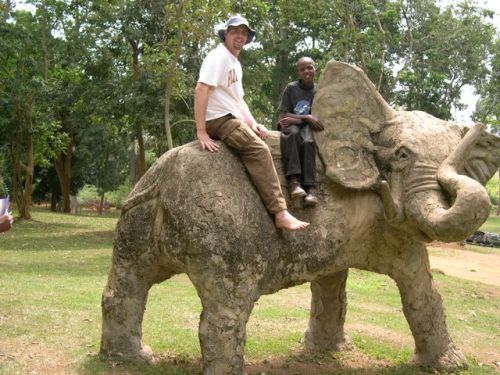

As the world listens to these words and reads them over again in the blogosphere, as we observe Obama’s actions and measure them against these words, we also react expressively. East Africans’ faith in Obama often literally makes a caricature of his campaign promises:

And, less creatively, tries to capitalize on his popularity:

But if the Professor President has anything tangible to offer the world, it will almost surely take the form of new directions that we never knew possible within the boundaries of our system…because that’s what it means to “form a more perfect union.”

For a boy who’s allergic to meat, Vincent sure does like to butcher animals and roast meat. I don’t get it; maybe he can sort of live vicariously through smell or something. Maybe he doesn’t miss it at all. I don’t get that either. Vegetarians escape my understanding. I’m an omnivore (excluding readers, of course).

For a boy who’s allergic to meat, Vincent sure does like to butcher animals and roast meat. I don’t get it; maybe he can sort of live vicariously through smell or something. Maybe he doesn’t miss it at all. I don’t get that either. Vegetarians escape my understanding. I’m an omnivore (excluding readers, of course).

The two men seated on a nearly perpendicular line to the larger group are basamize mediums. They’re kind of “staging possession” here. This is what I mean by a kusamira exhibition. They do all of the things they would normally do in any kusamira ritual: they tremble when the spirits grab their heads/bodies (“kwata ku mutwe”), they shout rhythmically as this is happening, and when they’re possessed their voices sound different, as they are the voices of the ancestors. The other performers greet the ancestors as they would greet their bajajja (grandparents), and they resume singing songs, now to welcome the spirits who have already come rather than to call spirits.

The two men seated on a nearly perpendicular line to the larger group are basamize mediums. They’re kind of “staging possession” here. This is what I mean by a kusamira exhibition. They do all of the things they would normally do in any kusamira ritual: they tremble when the spirits grab their heads/bodies (“kwata ku mutwe”), they shout rhythmically as this is happening, and when they’re possessed their voices sound different, as they are the voices of the ancestors. The other performers greet the ancestors as they would greet their bajajja (grandparents), and they resume singing songs, now to welcome the spirits who have already come rather than to call spirits.

Next week I’m going to a different village to work with some of the basawo from this group and some of their colleagues in a different district. Here’s where it gets interesting from a spiritual perspective: they’re preparing an end-of-year/Christmas celebration for the 23rd and 24th. Many of the people I work with practice Islam or Christianity, and nearly all celebrate Christmas no matter what their religious loyalties. It’s plainly not because the kids want presents on Christmas morning (they don’t really do that). Whatever their reasons, one thing is clear: everything from the rosaries people wear around their necks even as they welcome ancestral spirits to the celebration of holidays in multiple religious traditions indicates a kind of spiritual flexibility, a plurality uncommon in a world of increasing polarization and religious extremism. This is not merely tolerance; it’s a full-on embrace of two forces that collided head-on through colonization and missionization, and Uganda has the martyrs to prove it. As I move forward with this work, I wonder what that aspect of the village can teach us about being-in-the-world (as existential phenomenology would have it). What might these performances reveal about a village African gnosis and its value in the world?

Next week I’m going to a different village to work with some of the basawo from this group and some of their colleagues in a different district. Here’s where it gets interesting from a spiritual perspective: they’re preparing an end-of-year/Christmas celebration for the 23rd and 24th. Many of the people I work with practice Islam or Christianity, and nearly all celebrate Christmas no matter what their religious loyalties. It’s plainly not because the kids want presents on Christmas morning (they don’t really do that). Whatever their reasons, one thing is clear: everything from the rosaries people wear around their necks even as they welcome ancestral spirits to the celebration of holidays in multiple religious traditions indicates a kind of spiritual flexibility, a plurality uncommon in a world of increasing polarization and religious extremism. This is not merely tolerance; it’s a full-on embrace of two forces that collided head-on through colonization and missionization, and Uganda has the martyrs to prove it. As I move forward with this work, I wonder what that aspect of the village can teach us about being-in-the-world (as existential phenomenology would have it). What might these performances reveal about a village African gnosis and its value in the world?